For Black Death, a total of 159 epidemic events are known so far. It is an epidemic wave.

Table

| Page | DateStart date of the disease. | SummarySummary of the disease event | OriginalOriginal text | TranslationEnglish translation of the text | ReferenceReference(s) to literature | Reference translationReference(s) to the translation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1319-00-00-Bologna | 1319 JL | Epidemic | Al tempo della mortalità morì Folco Lombardi da Lucca e sepolto in S. | At the time of his mortality, Folco Lombardi of Lucca died and was buried in S. | Diario estratto dallo studio dell’ Alidosio, p. 35r | Translation by DeepL |

| 1345-00-00-Venice | 1345 JL | Origin of the Black Death and ravages in Venice | Anno Domini 1345, jnguiaria pestis, incipiens in partibus Tartarorum, et se, peccatis exigentibus, ad universum orbem contagiose extendens, adeo terribiliter desaevivit, quod penitus nulli loco perpercit; et si quando alicubi cessare videretur, transactis duobus, vel tribus annis, ad locum reverberatur eundem. | In the year of our Lord 1345, the pestilence, beginning in the regions of the Tartars, and spreading contagiously throughout the whole world, raged so terribly, driven by the demands of sin, that it spared no place entirely; and if it seemed to subside anywhere, after two or three years, it returned to the same place. | Raphaynus de Caresinis 1922, p. 5 | Translation by ChatGPT-3.5 |

| 1346-00-00-Bologna | 1346 JL | Epidemic in Bologna | Fu gran peste in Bologna, e morirno più di 4000 persone, fra quali morì Ms. Jacomo Bottivigari, Dottore di legge, Ms. Mraion da S. Marino Cavaliere, Salvadio Delfino, Bibozo Sava Medico. | There was a great plague in Bologna, and more than 4,000 people died, including Ms. Jacomo Bottivigari, Doctor of Law, Ms. Mraion da S. Marino Cavaliere, Salvadio Delfino, Bibozo Sava Medico. | Diario estratto dallo studio dell’ Alidosio, pp. 47r | Translation by DeepL |

| 1346-00-00-Golden Horde and adjacent territories Sim | 1346 JL | The first attack of the Black Death in the East, in Muslim countries and among the Tatars (Golden Horde), as well as other peoples living in these areas. | Toгo жe лѣтa [6854] кaзнь быcть oт Бoгa нa люди пoдъ вocтoчнyю cтpaнoю въ opдѣ и въ Opнaчи, и въ Capaи и въ Бeздeжѣ, и въ прочиxъ градѣxъ и cтpaнaxъ быcть моръ вeликъ на люди, на Бecepмeны и нa Taтapы, и нa Apмeны, и нa Oбeзы, и нa Жиды, и нa Фpязы, и нa Чepкacы, и нa прочaя чeлoвѣкы, тaмo живущaя въ ниxъ. Toль жe силенъ быcть моръ въ ниxъ, яко не бѣ мощно живымъ мepтвыxъ погрѣбати. | In the same year (1346)<a href="#cite_note-1">[1]</a> the punishment from God was [sent] on the people of the eastern part, in the Horde, on Old Urgench<a href="#cite_note-2">[2]</a>, and on Sarai<a href="#cite_note-3">[3]</a>, and on Bezdezh<a href="#cite_note-4">[4]</a>, and and in other towns and districts the plague was great among the people. There was a strong plague among the Muslims, and among the Tartars, and among the Armenians, and among the Abkhazians/Georgians, and among the Jews, and among the Franks/Latins, and among the Circassians, and among other people living there. The plague was so strong that it was impossible for the living to bury the dead. | Симеоновская летопись, in: Полное Cобрание Pусских Летописей, vol. XVIII, Mocквa: Знак, 2007, p. 95. | None |

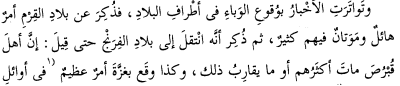

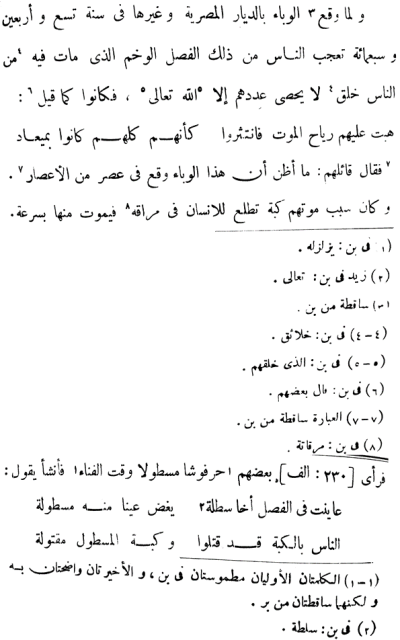

| 1346-04-00-the Horde | April 1346 JL | In 747 H (April 24, 1346 to April 12, 1347), the Black Death spread in the Horde (bilād Uzbak), where many people died in villages as well as towns. Plague then arrived in Crimea where the maximum daily death toll amounted to ca. 1,000, as the author, Ibn al-Wardī, was told by a trustworthy merchant. Afterwards, plague spread to Asia Minor (Rūm) where it killed many people. An Aleppine merchant who had returned from Crimea reported to Ibn al-Wardī that the judge (qāḍī) of Crimea had said that they had counted the deceased and that the number had amounted to 85,000 known plague deaths. The plague reached Cyprus, too, and the death toll was enormously high there as well. | Ibn al-Wardī - Tatimmat al-Mukhtaṣar 1970, vol. 2, p. 489 | Translation needed | ||

| 1347-00-00-Central Asia | 1347 JL | Fire comes out of the earth or falls from heaven in Central Asia as a reason for the outbreak of the Black Death. | Avemmo da mercatanti genovesi, uomini degni di fede, che avieno avute novelle di que' paesi, che alquanto tempo inanzi a questa pistilenzia, nelle parti dell' Asia superiore, uscì della terra, overo cadde da cielo un fuoco grandissimo, il quale stendendosi verso il ponente arse e consumò grandissimo paese sanza alcun riparo. E alquanti dissono che del puzzo di questo fuoco si generò la materia corruttibile della generale pistolenzia: ma questo non possiamo acertare. Apresso sapemmo da uno venerabile frate minore di Firenze vescovo di ..... de Regno, uomo degno di fede, che s'era trovato in quelle parti dov'è la città del Lamech ne' tempi della mortalità, che tre dì e tre notti piovvono in quelle paese biscie con sangue ch' apuzzarono e coruppono tutte le contrade:sc e in [p. 15] quella tempesta fu abattuto parte tel tempio di Maometto, e alquanto della sua sepoltura. | We have had from Genoese merchants, men worthy of faith, who have had news of those countries, that some time before this pistilenzia, in the parts of Upper Asia, a great fire came out of the earth, or fell from the sky, which, spreading towards the west, burned and consumed a great country without any shelter. And some say that from the stench of this fire was generated the corruptible matter of the general conflagration: but this we cannot ascertain. Later we learned from a venerable friar minor of Florence, bishop of ..... of the Kingdom, a man worthy of faith, who had been in those parts where the city of Lamech is in the times of mortality, that three days and three nights it rained in that country snakes with blood that apuzzarono and covered all the countries; and in [p. 15] that storm was torn down part of the temple of Muhammad, and some of his burial place. | Template:Matteo Villani 1995, vol. 1, pp. 14–15. | Translation by DeepL |

| 1347-00-00-China | 1347 JL | The Black Death with presumed origins in China or Ethiopia, spreading to Syria and Egypt. Discussion of its spread via Caffa and Constantinopel, Genoa and reaching the Iberian Peninsula. | Die Meinungen über die Herkunft dieses Ereignisses gehen auseinander. Der Gewährsmann erwähnte nach dem Zeugnis mancher christlichen Kaufleute, die nach Almeriah kamen, daß die Krankheit in dem Lande Hata entstanden sei; Hata heißt in der persischen Sprache China, wie ich es von einem Gewährsmann aus Samarkand gelernt habe. China ist die Grenze der bewohnten Erde nach Osten zu. Die Seuche ist in China verbreitet und von da aus ist sie nach dem persischen Irak, den türkischen Ländern gewandert. Andere erwähnten nach dem Bericht christlicher Reisenden, daß sie in Abessinien entstanden sei und von dort aus in die Nachbarländer bis nach Ägypten und Syrien vorgedrungen sei. Diese verschiedenen Berichte beweisen, daß die Katastrophe allgemein alle Länder und Zonen heimgesucht hat. Der Grund der Verschiedenheit der Berichte ist, daß, wenn sie in einem an der (p. 42) Grenze der Erde liegenden Lande erscheint, dessen Einwohner denken, daß die Krankheit dort entstanden sei; und von dort aus verbreitet sich diese Ansicht. Es ist uns auch von vielen Seiten berichtet worden, daß sie in der genuesischen Festung Kaffa gewesen sei, die unlängst durch ein Heer von mohammedanischen Türken und Romäern belagert wurde, dann in Pera, dann in dem großen Konstantinopel, auf den Inseln von Armania an der Küste des Mittelmeeres, in Genua, in Frankreich. Sie griff weiter über nach dem fruchtbaren Andalusien, überschwemmte die Gegenden von Aragon, Barcelona, Valencia u. a., verbreitete sich in dem größten Teil des Königreichs Kastilien bis Sevilla im äußersten Westen, erreichte auch die Inseln des Mittelmeeres Sizilien, Sardinien, Mallorca, Ibiza, sprang über nach der gegenüberliegenden Küste von Afrika und ging von da aus weiter nach Westen. | Opinions differ as to the origin of this event. According to the testimony of some Christian merchants who came to Almeriah, the author mentioned that the disease originated in the land of Hata; Hata means China in the Persian language, as I learnt from an author from Samarkand. China is the border of the inhabited earth to the east. The disease spread in China and from there it travelled to Persian Iraq and the Turkish countries. Others mentioned, according to the report of Christian travellers, that it originated in Abyssinia and from there spread to neighbouring countries as far as Egypt and Syria. These different reports prove that the catastrophe affected all countries and zones in general. The reason for the diversity of reports is that when it appears in a country lying on the (p. 42) frontier of the earth, its inhabitants think that the disease originated there; and from there this opinion spreads. It has also been reported to us from many quarters that it was in the Genoese fortress of Kaffa, which was recently besieged by an army of Mohammedan Turks and Romæans, then in Pera, then in the great Constantinople, on the islands of Armania on the coast of the Mediterranean, in Genoa, in France. It spread further to fertile Andalusia, flooded the regions of Aragon, Barcelona, Valencia and others, spread through most of the kingdom of Castile as far as Seville in the far west, reached the Mediterranean islands of Sicily, Sardinia, Mallorca, Ibiza, jumped over to the opposite coast of Africa and from there continued westwards.. | Dinanah 1927, pp. 41-42 | Translation by Martin Bauch |

| 1347-00-00-Italy1 | 1347 JL | Spread of the Black Death across the Mediterranean into Italy and its major islands with processions emerging in Florence. | E stesesi la detta pistolenza infino in Turchia e grecia, avendo prima ricerco tutto Levante i Misopotania, Siria, Caldea, Suria, Ciptro, il Creti, i Rodi, e tutte l'isole dell'Arcipelago di Grecia, e poi si stese in Cicilia, e Sardigna, Corsica, ed Elba, e per simile modo tutte le marine e riviere di nostri mari; ed otto galee di Genovesi c'erano ite nel mare Maggiore, morendo la maggiore parte, non ne tornarono che quattro galee piene d'infermi, morendo al continuo; e quelli che giunsono a Genova, tutti quasi morirono, e corruppono sì l'aria dove (p. 487) arivavano, che chiunque si riparava co lloro poco apresso morivano. Ed era una maniera d'infermità, che non giacia l'uomo III dì, aparendo nell'anguinaia o sotto le ditella certi enfiati chiamati gavoccioli, e tali ghianducce, e tali gli chiamavano bozze, e sputando sangue. E al prete che confessava lo 'nfermo, o guardava, spess s'apiccava la detta pistilenza per modo ch'ogni infermo era abbandonato di confessione, sagramento, medicine e guardie. Per la quale sconsolazione il papa fece dicreto, perdonando colpa e pena a' preti che confessassono o dessono sagramento alli infermi, e lli vicitasse e guardasse. E durò questa pestilenzia fina a ... e rimasono disolate di genti molte province e cittadini. E per questa pistilenza, acciò che Iddio la cessasse e guardassene la nostra città di Firenze e d'intorno, si fece solenne processione in mezzo marzo MCCXLVII per tre dì. E tali son fatti i giudici di Dio per pulire i peccati de' viventi.. | This pestilence spread into Turkey and Greece, having first circled the Levant—Mesopotamia, Assyria, Chaldea, Syria, Cyprus, Crete, Rhodes, and all the islands of the archipelago of Greece—and then spread to Sicily, Sardinia, Corsica, and Elba and in like manner to all the shores and coasts of our seas. [When] eight Genoese galleys sailed into the Black Sea, the greater part of their crews died, and only four galleys returned, full of sick men who were dying one after another. Almost all those who reached Genoa died, and so corrupted the air where they landed, that whoever met with them died shortly afterward. This was the manner of the sickness: certain swellings appeared on the groin or below the armpits, swellings which some called gavoccioli and some ghianducce and some bozze, and which oozed blood. A man could not live for more than three days after they appeared. And this pestilence often attached itself to the priests who heard the confessions of the sick, or who looked after the sick, so that the sick were deprived of confession, sacrament, medicine, and watchers. This terrible problem led the pope to issue a decree, pardoning sin and penance to those priests who confessed or gave the sacrament to the sick, and who visited and watched over them. (p. 139) And this pestilence lasted until [. . .] and many provinces and cities were desolated. And in mid-March 1347, a solemn procession was held [every day] for three days, so that the Lord God might end this pestilence and Protect our city of Florence and its surroundings. ‘Thus do the judgments of God cleanse the sins of the living. Let us leave this matter, and speak somewhat of the deeds of the newly elected Emperor Charles of Bohemia. | Giovanni Villani 1990, vol. 3, pp. 487–488 | None |

| 1347-00-00-Lombardy | 1347 JL | Cold weather followed by famine. Then outbreak of the Black Death in parts of Lombardy, especially in rural areas, but also in Varese; plague spares Milan, Novara, Pavia, Cuneo and Vercelli. Source is notorious for confused, imprecise and contradictory chronology<a href="#cite_note-1">[1]</a> | Dixeram supra quod tunc temporis nix erat magna et fuit verum; nam duravit super facie terre usque ad finem raensis martii vel quasi, propter quam campestria tantum fastidium frigoris et undacionis susceperunt quod biada, nive recedente, ut plurimum mortua aparebant. Ex qua multe terre habitatoribus private fuerunt, maxime in montanis partibus; deinde, fame cessante, cepit morbus prosiliens a partibus ul'tramarinis partes inferiores invadere; et primo Bononiam applicuit, videlicet anno MCCCXLIIII, in qua civitate infiniti perierunt, omni defensione et medela destituta. Due partes autem corporum dicebantur periisse. Invasitque pestilencia Januam ubi simili modo perierunt; invasit Parmam in qua multi defecerunt. Servavit Mediolanum, Papiam, Novariam, Cumas, Vercellas, set discurrando occupavit Lombardiam a dicto anno usque annum MCCCXLVII, ubi iterum super districtu Novarie vigebat; nam in dicto districtu Momum vacuavit, Bellanzagum similiter et in Burgomanerio ', ubi conversationem habebam, ubi dicti viri belligeri habitabant, perlerunt dieta clade in tribus mensibus prò completis centenaria xxvii virorum, computatis mulieribus et parvulis, nec in aliìs terris tunc insilivit novariensibus; in comitatu autem Mediolani in partibus Varixii, Anglerie, Gallarate et circumstanciis ut supra, sine numero perierunt. Cessavit itaque dieta pestilentìa moriendi, tamen in aliquibus locis discurrendo. | I mentioned above that at that time there was a great snowfall, and it was true; for it lasted on the surface of the earth until the end of March or nearly so. Because of this, the fields suffered so much from the cold and flooding that, when the snow melted, most of the crops appeared dead. As a result, many lands were deprived of their inhabitants, especially in the mountainous regions. Then, as the famine ceased, a disease began to spread from the overseas regions, invading the lower areas. It first struck Bologna in the year 1344 (sic!), where countless people perished, lacking any defense or remedy. It was said that two-thirds of the population died. The pestilence then invaded Genoa, where many similarly perished, and then Parma, where many died as well. Milan, Pavia, Novara, Como, and Vercelli were spared, but the disease spread throughout Lombardy from that year until 1347 (sic!), when it again raged in the district of Novara. In that district, it emptied Momeliano, Bellinzona, and Borgomanero, where I lived, and where the mentioned warriors lived. In three months, 2,700 men perished, including women and children, and the disease did not attack other lands in Novara at that time. However, in the surroundings of Milan, in the regions of Varese, Angera, Gallarate, and the surrounding areas, countless people perished. Thus, the aforementioned pestilence ceased in its deadliness, though it continued to spread in some places | Cognasso 1926-39, p. 53. | Translation by Martin Bauch |

| 1347-00-00-Middle East | 1347 JL | Fire comes out of the earth or falls from heaven in Middle East and beginning of the Black Death at the mouth of the Don and in Trabizond. | Ma infinita mortalità, e che più durò, fu in Turchia, e in quelli paesi d'oltremare, e tra' Tarteri. E avenne tra' detti Tarteri grande giudicio di Dio e maraviglia quasi incredibile, e ffu pure vera e chiara e certa, che tra 'l Turigi e 'l Cattai nel paese di Parca, e oggi di Casano signore di Tartari in India, si cominciò uno fuoco uscito di sotterra, overo che scendesse da cielo, che consumò uomini, e bestie, case, alberi, e lle pietre e lla terra, e vennesi stendendo più di XV giornate atorno con tanto molesto, che chi non si fuggì fu consumato, ogni criatura a abituro, istendendosi al continuo. E gli uomini e femine che scamparono del fuoco, di pistolenza morivano. E alla Tana, e Tribisonda, e per tutti que' paesi non rimase per la detta pestilenza de' cinque l'uno, e molte terre vi s'abbandarono tra per la pestilenzia, e tremuoti grandissimi, e folgori. E per le lettere di nostri cittadini degni di fede ch'erano in que' paesi, ci ebbe come a Sibastia piovvono grandissima quantità di vermini [p. 487] grandi uno sommesso con VIII gambe, tutti neri e conduti, e vivi e morti, che apuzzarono tutta la contrada, e spaventevoli a vedere, e cui pugnevano, atosicavano come veleno. E in Soldania, in una terra chiamata Alidia, non rimasono se non femmine, e quelle per rabbia manicaro l'una l'altra. E più maravigliosa cosa e quasi incredibile contaro avenne in Arcaccia, uomini e femmine e ogni animale vivo diventarono a modo di statue morte a modo di marmorito, e i signori d'intorno al paese pe' detti segni si propuosono di convertire alla fede cristiana; ma sentendo il ponente e paesi di Cristiani tribolati simile di pistolenze, si rimasono nella loro perfidia. E a porto Tarlucco, inn-una terra ch'ha nome Lucco inverminò il mare bene x miglia fra mare, uscendone e andando fra terra fino alla detta terra, per la quale amirazione assai se ne convertirono alla fede di Cristo. | But the mortality was much greater and much more severe in Turkey and in Outremer, and among the Tartars. And a great judgment of God occurred among these Tartars, a marvel almost unbelievable but which was true, clear, and certain. Between the Turigi and the Cattai in the land of Parca, presently ruled by Casano, lord of the Tartars in India, a fire began to burn forth from the ground, or indeed to fall from the sky. It consumed men, animals, houses, trees, and (p. 138) the stones, and the earth, spreading a distance of more than fifteen days’ travel all around, with such great harm that those who did not flee were consumed—every creature and every inhabitant—as it ceaselessly spread. The men and women who escaped this fire died of pestilence. At Tana and Trebizond, and in all those lands, not one person out of five survived and many cities were abandoned because of the pestilence and terrible earthquakes and lightning. We learn from letters sent by trustworthy citizens of our city who were in those lands that a very great quantity of little worms rained down on Sibastia. Each was one span in length, colored black with eight legs and a tail. They fell both alive and dead and were terrifying to behold, filling the city with their stench, and those whom they stung were poisoned as with venom. In Soldania, in a city called Alidia, only the females remained and these [worms], driven by rage, ate one another. [The letters] tell of an even more marvelous and almost unbelievable thing that occurred in Arcaccia: men and women and every living animal became like dead statues of marble. Nearby lords saw these signs and considered converting to the Christian faith, but when they heard that the West and the Christian lands were suffering from these same pestilences, they persisted in their wickedness. At Porto Talucco, in a city called Lucco, the sea was filled for ten miles with worms that crawled out of the water and across the land all the way up to the city. Many people were so astonished by this that they converted to the faith of Christ. | Giovanni Villani 1990, vol. 3, pp. 486–487 | None |

| 1347-01-00-Piombino | January 1347 JL | Black Death in Piombino, but only a few deaths in Milan. | Il detto morbo s'atachò a Pionbino, inperochè vi venne cierti Genovesi di quelle maledette galee, e morivi e' 3 quarti de le persone in Pionbino; per tanto si fu per abandonare. Queste maledette galee de' Genovesi venivano e aveano aiutato a' Saraceni e al Turco a pigliare la città di Romania che era de' Cristiani che non féro i Turchi, e per questo si tenea che Dio avea mandato tanta mortalità a i detti Genovesi e a' Cristiani e in Turchia, e morì in Saracina e' tre quarti e così de' Cristiani. A Milano morì poca gente, inperochè morì 3 fameglie, le quali le case loro furo murate l'uscia e le finestre, chè nissuno v'entrasse. | The disease came to Piombino, because some Genoese from those cursed galleys came there, and three quarters of the people died in Piombino; therefore it was abandoned. These accursed galleys of the Genoese came and had helped the Saracens and the Turks to take the city of Romania, which belonged to the Christians, rather than the Turks, and for this reason it was believed that God had sent so much mortality to the said Genoese and the Christians and in Turkey, and three quarters died in Saracina and so of the Christians. In Milan few people died, for three families died, and their houses were walled up with doors and windows, so that no one could enter. | Agnolo di Tura del Grasso 1939, p. 553. | Translation by DeepL |

| 1347-09-00-Catania | September 1347 JL | Outbreak of the Black Death in Catania with detailed description of symptoms and social disintegration. Prominent victim of the plague is Duke Giovanni d'Aragona, Regent of the Kingdom of Trinacria/Sicily at the time. | Quid dicemus de civitate Cataniae, quae oblivioni tradita est? Tanta fuit pestis praedicta exorta in ea, quod non solum pustulae illae, quae "anthraci" vulgari vocabulo nuncupabantur, sed etiam glandulae quaedam in diversis corporum membris nascebantur, nunc in pectine, aliae in tibiis, aliae in brachiis, aliae in gutture. Quae quidem a principio erant sicut avellanae, et crescebant cum magno frigoris rigore, et in tantum humanum corpus extendebant et affligebant, quod diutius in se potentiam non habens standi, se ad lectum perferrebat, febribus immensis incitatus, et amaritudine non modica contristatus. Quapropter glandulae illae ad modum nucis crescebant, deinde ad modum ovi gallinae vel anseris, et quorum dolores non modici, et humorum putrefactione urgebant dictum humanum corpus sanguinem expuere; quod sputum, a pulmonibus infecto perveniens ad guttur, totum corpus humanum putrefaciebat: quo putrefacto, humoribus deficientibus, spiritum exalabant. Quae quidem infirmitas triduo perdurabat; quarto vero die ad minus a rebus humanis praedicta humana corpora erant adepta. Catanienses vero perpendentes talem aegritudinem sic brevi finire tempore, sicuti dolor capitis eis superveniebat, et rigor frigoris, omnia peccata eorum primo et ante omnia sacerdotibus confitebantur, et deinde testamenta eorum conficiebantur. Tanta erat in praedicta civitate condemnsa mortalitas, quod iudices et notarii se ad testamenta facienda ire recusabant. Et si ad aliquem infirmum accederent, ab eo procul omnino stabant. Sacerdotes ullatenus ad domos infirmorum accedere timore proximi mortis trepidabant. Tanta erat immensa mortalitas in civitate praedicta, quod iudices et notarii in conficiendis testamentis, nec sacerdotes ad peccatorum confitenda peccamina poterant totaliter continuo vacare. Patriarcha vero praedictus, volens de animabus Cataniensium providere, cuilibet sacerdoti, licet minimo, totam, quam habebat ipse episcopalem et patriarchalem licentiam, de absolvendis peccatis tribuit atque dedit. Quapropter omnes, qui deficiebant, secundum veram opinionem ad locum Dei tutam infallibiliter erant recepti. Dux vero Joannes praedictus timens mortem supradictam, nolens civitatibus et locis appropinquare habitatis propter aeris infectionem, per loca nemorosa et inhabitata, circumquaque se hinc inde continue versabatur. Sed dum hinc inde nunc ad aquam salis, quae est in nemore Cataniensi, nunc ad quamdam turrim, quae vocatur "Lu Blancu" per sex milliaria a civitate Cataniae distantem, nunc ad quandam ecclesiam sancti Salvatoris de Blanchardu in nemore civitatis praedictae, se quasi latitando discurreret, pervenit ad quamdam ecclesiam, seu locum per dictum Ducem noviter constructum [p. 568] vocatum sanctu Andria, qui locus est in confiniis nemoris Mascalarum; in quo dum incolumis ac sanus existeret, ex quadam sibi superveniente infirmitate mortuus extitit. Corpus cuius fuit sepultum in maiori Catanensi Ecclesia, in eo videlicet tumulo, ubi corpus quondam Friderici Regis patris sui fuerat conditum et humatum. Et hoc anno Domini MCCCXLVIII, de mense Aprilis primae Indictionis. Quae quidem mortalitas duravit a mense Septembris dictae primae Indictionis usque ad mortem Ducis supradicti paulo ante vel post. Talis itaque gravis fuit mortalitas in nullo dispar sexu, in nulla aetate dissimilis, generaliter cunctos iugiter affecit, ut etiam quos non egit in mortem, turpi macie exinanitos afflictosque dimisit atque relaxavit. In qua mortalitate fuit dictus Patriarcha mortuus, et sepultus in maiori Catanensi Ecclesia, anima cuius in pace quiescat. | What shall we say of the city of Catania, which has been consigned to oblivion? Such was the plague that arose there that not only did those pustules called "anthraces" in the common tongue appear, but also certain swellings in various parts of the body—now on the chest, some on the shins, others on the arms, and others in the throat. These, at first, were like hazelnuts, and they grew with a great chill and afflicted the human body so severely that, unable to stand any longer, the person would collapse onto the bed, overcome by intense fevers and burdened with great bitterness. As a result, those swellings would grow to the size of a walnut, then to the size of a hen's egg or even a goose's egg, and the pain was unbearable. The rotting of bodily fluids caused the afflicted person to spit blood; this sputum, infected from the lungs and reaching the throat, would completely decay the entire body. Once the body had decayed and the fluids had been drained, the person would exhale their spirit. This disease would last three days; by the fourth day, at the latest, the person would succumb. The people of Catania, observing that such an illness would end so quickly, often experienced severe headaches and chills. In this state, they confessed all their sins, first and foremost, to priests, and then prepared their wills. The mortality in the aforementioned city was so severe that judges and notaries refused to go to prepare the wills. And if they did approach any of the sick, they kept a great distance. Priests, too, were afraid to approach the homes of the sick out of fear of their own impending deaths. The mortality in the city was so immense that judges and notaries could not keep up with preparing wills, nor could priests attend continuously to the confession of sins. The Patriarch, seeing the need to provide for the souls of the people of Catania, granted to each priest, even the humblest, the full authority of his episcopal and patriarchal license to absolve sins. Because of this, all who died were, according to true belief, received into the secure presence of God. Duke Giovanni [di Randazzo/d'Aragona, 1317-1348], fearing the aforementioned plague and not wanting to approach inhabited cities or places due to the infection of the air, moved about continuously through forested and uninhabited areas. Wandering from one place to another, he would sometimes go to the Salt Spring in the forest near Catania, sometimes to a tower called "Lu Blancu," six miles from the city of Catania, or to a church called S. Salvatoris de Blanchardu in the forest of the aforementioned city. While wandering in hiding, he eventually came to a church or location newly constructed by the Duke, called S. Andrea, which is situated on the borders of the Mascalarum forest. While living there in good health, he was overtaken by a sudden illness and died. His body was buried in the major church of Catania, in the very tomb where the body of Frederick, King and his father, had been buried and laid to rest. This happened in the year of our Lord 1348, in the month of April, during the first Indiction. This mortality lasted from September of the same first Indiction until shortly before or after the death of the aforementioned Duke. Such a grave mortality affected all, regardless of sex or age, and struck everyone continuously. Even those whom it did not bring to death were left emaciated and afflicted with a wretched gauntness, ultimately releasing them in a weakened state. During this mortality, the aforementioned Patriarch also died and was buried in the major church of Catania, and may his soul rest in peace. | Michele da Piazza 1791, pp. 567-568. | Translation by Martin Bauch |

| 1347-10-00-Messina | October 1347 JL | Arrival of the Black Death in Messina, Sicily on board of Genoese ships. | Caput XXVII. De repentina mortalitate orta in Regno Sicilie & quo tempore duravit, & quid actum eo tempore extitit [...] Accidit ergo, quod de mense octobris anno dominice incarnationis MCCCXLVII circa principium mensis octobris prime indictionis, duodecim galee januensium, divinam fugientes ulcionem, quam Dominus noster pro eorum iniquitatibus desuper eis transmiserat, applicuerunt in portum civitatis Messane, talem secum morbum ossibus infixum deferentes, quod si quis cum aliquo ipsorum locutus fuisset , erat infirmitate effectus letali, quam mortem nullatenus evadere poterat inmediate. Signa vero mortis ianuensium et messanensium cum eis participantium talia erant. Quod propter infectionem hanelitus inter eos mixti universaliter alloquentes , adeo unus alterum inficiebat , quod quasi totus dolore concussus videbatur, et quodammodo conquassatus; ex cujus doloris conquassatione, et hanelitus inficatione oriebatur quedam pustula circa femur , vel brachium ad modum lenticule. Que ita inficiebat et penetrabat corpus, quod violenter spuebant sanguinem: quo sputo spuendo per triduum, incessanter sine aliqua cura curabili vitam expirabant; et non tantum moriebantur quicumque eis conversabantur, ymmo quicumque de rebus eorum 63) emeret, tangeret, seu affectaret. Messanenses vero cognoscentes dictam eorum repentinam mortem eis incurrere propter januensium galearum adventum, eos de portu et civitate predicta cum festinantia maxima expulerunt. Remansitque dicta infirmitas in civitate predicta, ex qua sequuta extitit immensa mortalitas. Et in tantum unus alium habebat exosum, quod si filius de morbo predicto infirmabatur, pater sibi adherere penitus recusabat; et si ad eum ausus esset appropinquare, adeo infectus erat morbo predicto, quod mortem nullatenus evadere poterat, quin per triduum suum spiritum non exalaret. Et non tantum solus ipse de domo moriebatur, sed omnes familiares in eadem domo astantes, catuli, et animalia in dicta domo existentia patrem familias mortui sequebantur. Et intantum mortalitas ipsa Messanensibus invaluit, quod petebant multi sacerdotibus confiteri sua peccata, et testamenta conficere, et sacerdotes, judices et notarii ad domos eorum accedere recusabant; et si aliqui ipsorum ad eorum hospitia ingrediebantur pro testamentis, et talibus conficiendis, mortem nullatenus repentinam poterant (p 83) evitare. Fratres vero Ordinis minorum et Predicatorum et aliorum ordinum accedere volentes ad domos infirmorum predictorum, et confitentes eisdem de eorum peccatis, et dantes eis penitentiam juxta velle sermus. divinam justitia, adeo letalis mors ipsos infecit, quod fere in eorum cellulis de eis aliqui remanserunt. Quid ultra? Cadavera stabant sola in hospitiis propriis, nullus sacerdos, filius, sive pater, atque consanguineus ausus erat in eisdem intrare, sed tribuebant bastatiis non modicam pensionem pro cadaveribus in sepultura deferendis predictis. Hospitia defunctorum remanebant aperta, et patentia cum omnibus jocalibus, pecunia, et thesauris; adeo ut si quis ingredi vellet, aditus a nullo proibitus erat. Nam tanta subito pestilentia exorta est, ut ministri quoque primum non sufficerent, deinde non essent. Quapropter Messanenses hunc casum terribilem et monstruosum intuentes, migrare de civitate quam mori potius elegerunt; et non solum in urbem veniendi, sed etiam appropinquandi ad eam negabatur. In aeris et in vineis extra civitatem cum eorum familiis statuerunt mansiones. Aliqui vero et pro majori parte in civitatem Catanie perrexerunt, confisi quod beata Cataniensis Agatha virgo eosdem tali infirmitate liberaret. Inclita regina Helisabeth regina Sicilie, existens in civitate Catanie, don Fridericum filium suum, qui in civitate Messane tunc temporis aderat, ad se festinante jussit venire; qui cum galeis venetorum Cataniam festinanter applicuit. | Chapter XXVII: On the sudden mortality that arose in the Kingdom of Sicily, the duration of that time, and what happened during that time Therefore, it happened that in the month of October in the year of our Lord's Incarnation 1347, around the beginning of October, twelve Genoese galleys, fleeing divine retribution which our Lord had sent upon them for their sins, docked at the port of the city of Messina. They brought with them a disease so deeply embedded in their bones that if anyone spoke with any of them, they were struck with a fatal illness from which they could not escape immediate death. The signs of death among the Genoese and those of Messina who interacted with them were such that, because of the infection from their breath, mingling with them universally, one infected another so that it seemed as if they were entirely shaken by pain, and in a way crushed by it; from this crushing pain and the infection from their breath, there arose pustules around the thigh or arm, like a lentil. These pustules infected and penetrated the body so violently that they coughed up blood; and with this coughing up of blood for three days, constantly without any cure, they expired; and not only did those who interacted with them die, but also anyone who bought, touched, or desired any of their belongings (page 563). The people of Messina, recognizing that this sudden death was befalling them because of the arrival of the Genoese galleys, expelled them from the port and the aforementioned city with the greatest haste. The aforementioned disease remained in the aforementioned city, resulting in immense mortality. To such an extent did one hate another, that if a son fell ill from the aforementioned disease, the father entirely refused to stay near him; and if he dared to approach him, he was so infected by the aforementioned disease that he could not escape death and would expire within three days. And not only did the individual in the house die, but all the family members present in the same house, including pets and animals in the house, followed the head of the dead family. The mortality increased so much among the people of Messina that many asked priests to confess their sins and make their wills, but priests, judges, and notaries refused to go to their houses; and if any of them entered their houses to make wills and other such documents, they could not avoid sudden death. Friars of the Order of Minors and Preachers and members of other orders, wishing to go to the houses of the aforementioned sick people, confessing their sins and giving them penance according to divine justice, were so lethally infected that almost none of them remained in their cells. What more? Corpses lay alone in their homes, no priest, son, father, or relative dared to enter them, but they paid considerable sums to others to bury the bodies. The houses of the deceased remained open and unguarded with all their jewels, money, and treasures; so that if anyone wished to enter, the entrance was prohibited by no one. Such a sudden pestilence arose that at first there were not enough servants, and eventually, there were none. Therefore, the people of Messina, seeing this terrible and monstrous event, chose to migrate from the city rather than die; and not only was it forbidden to come into the city, but also to approach it. They set up camps in the air and vineyards outside the city with their families. Some, and for the most part, went to the city of Catania, believing that blessed Agatha of Catania would free them from such an illness. The noble Queen Elisabetta, Queen of Sicily, residing in the city of Catania, hastily summoned her son Federico, who was then in the city of Messina, to come to her; and he hurried to Catania with Venetian galleys. | Michele da Piazza 1980, pp. 82-83 | None |

| 1347-10-00-Messina2 | October 1347 JL | Procession to counter the outbreak of the Black Death in Messina fails. | Cap. 29: Quomodo Messanenses adcesserunt ad beatam Maria de Scalis cum sacerdotali officio; et que signa, et miracula apparuerunt ibidem et de mortalitate in civitate Catanie, et de morte Ducis Joannis. Messanenses vero de hujusmodi mira visione territi, miro modo sunt universaliter effecti timidi. Quapropter ad beatam Virginem de Scalis per miliaria sex a civitate Messane distantem, scalciatis pedibus, cum processione sacerdotali, comuniter ambulare statuerunt. Ad quam appropinquantes Virginem, omnes unanimiter in terris fixerunt devotissime genua, cum lacrimis, Dei et beate Virginis clamantes subsidium; et ingredientes in ecclesiam supradictam, devotis orationibus, et sacerdotali cantilena divina clamantes, miserere nostri Deus, quamdam ymaginem matris Dei sculpitam, ibidem antiquitus constitutam, propriis manibus appreenderunt. Quam in civitatem Messanem elegerunt ingredi facere, propter cujus visionem et ingressionem putabant demonia a civitate eicere, et a tali mortalitate penitus liberari. Propter quod elegerunt quendam sacerdotem ydoneum dictam ymaginem super quodam equo in brachiis suis honorifice apportare. Et reveretentes ad dictam civitatem cum ymagine supradicta, dicta sacra Dei mater, dum vidit et appropinquavit da dictam civitatem, adeo sibi exosam reputavit, et totaliter peccatis sanguinolentam, quod post tergum reversa, non tantum intrare noluit in civitatem, sed ipsam aborruit oculis intueri. Propter quod tellus aperta extitit in profundum, et equus, super quo dicta Dei matris ferebatur ymago, fixus et immobilis extitit sicut petra, et precedere, vel retrocedere non valebat. | Chapter 29: How the People of Messina Approached the Blessed Mary of the Stairs with Priestly Devotion; the Signs and Miracles that Appeared There; and the Plague in the City of Catania, Along with the Death of Duke John. The people of Messina, terrified by such a miraculous vision, were universally struck with great fear. Therefore, they resolved to walk barefoot, in a solemn priestly procession, to the Blessed Virgin of the Stairs, located six miles from the city of Messina. When they approached the Virgin, they all fell unanimously to their knees on the ground with great devotion, crying out with tears for the help of God and the Blessed Virgin. Entering the aforementioned church, they prayed devoutly and sang divine hymns with priestly chants, calling upon God with the words, "Have mercy on us, O God." In the church, they took hold of a carved image of the Mother of God, which had been placed there in ancient times. They decided to bring this image into the city of Messina, believing that her presence and entry into the city would drive out demons and completely free the city from the plague. To this end, they selected a suitable priest to carry the image with reverence in his arms on horseback. However, as they returned to the city with the sacred image, the Holy Mother of God, upon seeing and approaching the city, found it so abhorrent, deeming it bloodstained with sin, that she turned her face away. Not only did she refuse to enter the city, but she also avoided even looking at it. Because of this, the earth opened to a great depth, and the horse carrying the image of the Mother of God became fixed and immovable, like a rock, unable to advance or retreat. | Michele da Piazza 1980, pp. 82-83. | None |

| 1347-10-00-Messina3 | October 1347 JL | Most plague refugees from Messina fail to enter Catania and spread the Black Death to Siracusa, Agrigento and Trapani. | Quid ultra? Adeo fuerunt abominabiles & timorosi, quod nemo cum eis loquebatur, nec conversabant, sed fugiebant velociter eorum visionem, eorum anelitus penitus recusantes, & quasi in derisione omnibus Cataniensibus sunt effecti. Et si aliquis eorum cum aliquo loquebatur, respondebat sibi vulgariter, non mi parlari ca si Missinisi, & nemo eos hospitabatur. Domos pro eorum habitaculis ad conducendum penitus non inveniebant. Et nisi quod Messanenses aliqui in civitate Catanie cum eorum familia habitantes eos clam hospitabantur, fuissent quasi omni auxilio destituiti. Disperguntur itaque Messanenses per univerfam insulam Sicilie, & pergentes in civitatem Siracusie, adeo illa egritudo sic infecit Siragusanos, quod diversos immo immensos letaliter interfecit; terra Xacce, terra Trapani, & civitas Agrigenti. | What more? They were so abominable and feared that no one would speak to them or interact with them; instead, people fled swiftly from their sight, completely avoiding their breath, and they became a subject of mockery to all the people of Catania. And if any of them spoke to someone, they would be answered rudely, "I don’t speak to those from Messina." No one would give them shelter. They could not find houses to rent as living quarters. If it had not been for some Messinese families living in the city of Catania who secretly hosted them, they would have been completely without help. Thus, the Messinese dispersed throughout the entire island of Sicily, and when they reached the city of Syracuse, the plague so thoroughly infected the Syracusans that it lethally afflicted many, even in great numbers. The lands of Sciacca, Trapani, and the city of Agrigento were similarly affected. | Michele da Piazza 1791, p. 566. | Translation by Martin Bauch |

| 1347-11-00-Genoa | November 1347 JL | Genoese galleys spread the Black Death in Genoa and Sicily. | Le galee de' Genovesi tornaro d'oltremare e da la città di Romania a dì ... di november e tornaro con molta infermità e corutione d'aria la quale era oltremare, in perrochè in quel paese d'oltremare morì in questo tenpo grande moltitudine di gente di morbo e pestilentia. Essendo gionte a Gienova le dette galee tenero per la Cicilia e lassorovi grande infermità e mortalità, che l'uno non potea socorare l'altro; e così gionti a Gienova di fatto v'attacoro il detto morbo e per questo tutti quelle navili furono tutti cacciati di Genova. | The galleys of the Genoese returned from overseas and from the city of Romania on dì ... of November, and returned with much infirmity and corruption of the air which was overseas, for in that overseas country a great multitude of people died of disease and pestilence at that time. When they reached Gienova, the said galleys sailed to Cicilia, and there they left great infirmity and mortality, so that the one could not support the other; and so when they reached Gienova, they attacked the said disease there, and for this reason all those galleys were expelled from Genoa. | Agnolo di Tura del Grasso 1939, p. 553. | Translation by DeepL |

| 1347-11-00-Italy | November 1347 JL | Arrival of the Black Death in Genoa and spread across Italy; but Parma and Milan remain almost untouched | Nelle parti oltra mora per più sei mesi fu grandissima pestilenza, la quale dalle galee de' Genovesi fu portata in Italia; e furono a Genova ricevute del mese di Novembre le prefate galee, sulle quali, prima che arivassero a Genova, era morta di questa mala influenza la maggior parte di coloro, che vi erano sopra: il rimanente morì quasi subito che furono in Porto e patria loro, questa infermità si allargò nella Citta, & infiniti ne morivano il giorno, & in breve per ogni Città di Lombardia, di Toscana, della Marca, della Puglia, e per ogni terra d'Italia si estese. E fu grandissima due anni continui, per la quale molte Città d'Italia furono distrutte; e sole Parma, e Milano pochissimo ne senterono; ma si sparse oltra monti, in Provenza, in Francia, in Aragona, in Spagna, in Anglia, in Alemagna, in Boemia, in Ungheria. | In the parts beyond the sea, for more than six months, there was a great pestilence, which was brought to Italy by the Genoese galleys; and in November, the aforementioned galleys were received in Genoa, on which, before they arrived in Genoa, the majority of those on board had died from this bad influence: the rest died almost immediately upon reaching their port and homeland. This disease spread in the city, and countless people died each day, and soon it extended to every city in Lombardy, Tuscany, the Marches, Apulia, and throughout all of Italy. It was exceedingly severe for two continuous years, during which many cities in Italy were destroyed; only Parma and Milan felt it very little; but it spread beyond the mountains, into Provence, France, Aragon, Spain, England, Germany, Bohemia, and Hungary | Giovanni di Cornazano 1728, col. 746 | Translation by Martin Bauch |

| 1347-11-00-Italy1 | November 1347 JL | Societal consequences of the Black Death across Italy | anzi tutto il Mondo sì Cristiani, com Infedeli ne furono infetti, e furono da servi, da' Medici, da' Notari, da' Preti, e Frati, abbandonati gl' Infermi, tal che non erano serviti nè curati, nè potevano testare, nè confessi o contriti assoluti morire i miseri Apestati. La cagione di ciò era, che subito che s'apressavano a gl'Infermi, cadevano in cotale disavventurata peste, e morivano per lo più di subito, tanto che molti insepolti restavano, e l'uno, e l'altro abbandonato laiciava, nè conoscevasi che Padre avesse Figluoli, nè Moglie Marito, nè Amico compagno, e quantunque molti ricchi morissero, non erano allora pronti gli heredi a cercare i posessi dell facultadi; anzi senza prezzo era tutta la richezza tenuta; nè più si conosceva gli avari avere l'oro più che la vita caro. Cosa horribile a vedere, che gli huomini abbandonando gli huomini, gli odi, le invidie, le lascive, le facoltà, l'amore terreno, tutti volti in timore d'horrida e spaventevole morte. | The whole world, both Christians and infidels, were infected, and the sick were abandoned by servants, doctors, notaries, priests, and friars, so that they were neither served nor cared for, nor could they make a will, nor die confessed or absolved, the miserable plague victims. The reason for this was that as soon as they approached the sick, they fell into such unfortunate pestilence and died almost immediately, so that many remained unburied, and one and the other abandoned each other, and it was not known that a father had children, nor a wife a husband, nor a friend a companion. And although many rich people died, the heirs were not then ready to seek their possessions; rather, all wealth was held without value, and it was no longer known that the avaricious held gold dearer than life. It was horrible to see that humans, abandoning humans, hatreds, envies, lusts, possessions, and earthly love, all turned to fear of a horrible and frightening death | Giovanni di Cornazano 1728, col. 746 | Translation by Martin Bauch |

| 1348-00-00-Apulia | 1348 JL | The Black Death hits Apulia and other parts of Southern Italy like Calabria. King Louis the Great of Hungary flees back home from the epidemic outbreak | sequitur annus qui nostre salutis MCCCXLVIII numeratur, in quo pestis iam pridem cepta insigni strage per universam pene Italiam desevire cepit. Que, cum iam Brutios et Calabros ac universum Apulie Regnum inficere cepisset, et in dies magis obrepert, tantaque augmenteratur sevitia, ut solo contactu passim vulgaret morbos, et tabe ac pestifero odore inficeret validos, et egros biduo aut minori temporis spatio (p. 12) conficeret, ingens mortis formido Ludovicum, Ungarie regem, invasit, qua deterritus in Pannoniam aufugere quam celerrime constituit. | Matteo Palmieri 1918, pp. 11-12 | Translation needed | |

| 1348-00-00-Aquila | 1348 JL | About the Black Death in Aquila and beyond. | Lasso questa materia, retorno a l’altra tema, / e comeme de dicere d’una crudele stema: / tamanta fo mortalleta, non è omo a chi non prema, / credo che le duj parti de la genta fo asema. / Ma no fu solu in Aquila, ma fo in ogni contrada, / no tanto fra Cristiani, m’a‘ Sarracini è stata; / sì generale piaga mai no fo recordata / dal tenpo del diluvio, della gente anegata. |

I’ll leave this matter behind and change my topic / And it seems like talking about a great infortune / mortality was so great it preoccupied all people / I think two thirds of all people died. It wasn’t only in Aquila, but in all parts [of the world] / not only among Christians, but also with the Muslims. / nobody remembered such a general plague / since people drowned in the time of the deluge. |

Buccio di Ranallo, p. 240. | Translation by Martin Bauch |

| 1348-00-00-Aquila1 | 1348 JL | About the fear the Black Death in Aquila spread amongst doctors and how expensive medicine and medical products became. | E corsece uno dubio, ca mai lo odì contare, / che no volia li medeci l’infirmi visitare; / anche vetaro li omini che no lli deia toccare, / però che la petigine se lli potea iectare. Punamo che lli medici all’infirmi no giero, / ma pur de loro, dico, le duj parti morero; / li speziali medemmo che llo soperchio vennero, / de questa granne piaga più che li altri sentero. Mai no foro sì care cose de infermaria: / picciolu pollastregliu quatro solli valia, / e l’obu a duj denari e atri se vennia, / della poma medemmo era gra‘ carestia. Cose medicinali ongi cosa à passato, / ché l’oncia dello zuccaro a secte solli è stato; / l’oncia delli tradanti se‘ solli è conperato, / e dello melecristo altro tanto n’è dato. La libra dell’uva passa tri solli se vennia, / li nocci delle manole duj solli se dagia / dece vaca de mori un denaro valia, / quanno n’aviano dudici bo‘ derrata paria. |

As I said even the doctors refuse to see the ill / and yet, I tell you, two third of them died, too / and also the pharmacists selling medicine / felt this great plague more than others. As I said even the doctors refuse to see the ill / and yet, I tell you, two third of them died, too / and also the pharmacists selling medicine / felt this great plague more than others. Never before had medicine been so expensive: / Small, young chicken costed four soldi each / an eggs were sold for two to three soldi / and there was general dearth of apples. Medical products became expensive beyond any limit / one ounce of sugar costed seven soldi / one ounce of dragante (medical resin) rose to six soldi / and medical sugery syrup was even more expensive. One pound of grapes rose to three soldi / almonds were sold for two soldi / Ten blackberries costed one penny / and if you could have twelve it seemed like a good price. |

Buccio di Ranallo, pp. 240, 242. | Translation by Martin Bauch |

| 1348-00-00-Aquila2 | 1348 JL | About how wax became expensive and was regulated in use during funeral cerimonies while the Black Death ravaged in Aquila. | E della cera, dico, credo che abiate intiso, / se ne fosse u‘ romeio, lo quale vi fo priso: / a lo quarto de l’omini no fora ciro aciso / se omo avesse u‘ firino nella libra dispiso. Fo facto una ordenanza: che li homini acactasse / le ciri delle iclese e co‘ quilli pasasse, / e li altri poverelli canele no portasse: / dalle eclescie tolzéseli e li clirici acordasse. L’uomo che solia avere trenta libre de cera, / co‘ tre libra passavase per questa lor manera, / co‘ meza libra l’uomo che povero era; / acordava li clerici la domane o la sera. LCon tucto ’sto romegio la cera fo rencarata; / a vinti solli la libra li omini à conparata, / a dicidocto e a sidici, a dicisecte è stata, / quanno revende a quinici fo tenuta derrata. Anche a quisto romegio la cera no vastava, / se no fosse quillu ordine che li clerici usava; / con tanto pocatellio lu morto s’ofiziava, / tri volte le canele alla caia apicciava. |

And when it comes to wax, as you might have guessed, / there was no remedy to be found: / A quarter of all people had no acces to wax at all / (unclear translation) There was an ordinance: People should accept / the wax from churches, what was assigned to them / and all the other poor should have no candles: / they should take it from tchurches, the clergy agreed. A man who used to have thirty pounds of wax / now had only three pounds in this manner / and a poor man only half a pound of wax. / The funeral took place the same or the next day, as clergy agreed upon. With all this regulation, wax became expensive: / people bought it for twenty soldi a pound / it had been between sixteen and eighteen, / if you could buy it for fifteen, you were lucky. But also with this regulation, the wax was not sufficient, / if the clergy hadn’t established another order: / With so little the funeral had to take place, / that candles were lit only three times during the ceremony. |

Buccio di Ranallo, p. 242. | Translation by Martin Bauch |

| 1348-00-00-Aquila3 | 1348 JL | About changing participation of funeral ceremonies while the Black Death ravaged Aquila. | Quanno era l’uomo morto, ch’a santi lu portavano, / infi‘ ch’era a la ’clesia, clirici no cantavano, / e poi ch’erano dentro, così poco pasavano: / duj versi e duj respunzi e poi lu socterravano. Anche fu uno statuto: a l’omo che moresse / chi visse no sonasse che omo nos se inpauresse, / e fore de castellio omo a morto no gesse, / accìo che li corructi la gente no sentesse. Or vi dirrò lu mudo ch’era no correctare: / a un citolu de lacte più se solea fare; / de granni della terra, quanno potia adunare / vinti persone insemora, pariali troppo fare. No se tenia lu modo che sse solia tenere; / lu dì che morio l’omo, faceanolu jacere / perfi‘ a l’altra domane, per più onore avere, / le castella invitavaci che gisse a conparere. Quanno fo ’sta mortauta, nell’ora che moria, / in quel’ora medemma in ecclesia ne gia; / in quillu dì medemmo vigilia non avia, / non era chi guardarelu, però se sopellia. |

And when the dead person was taken to church / the clergy didn’t sing until they reached it / and once they were inside, they really did little: / two verses and two responsories and then they buried the dead person. There was another statute: For the dead person / no bells were rung as people might feel afraid / and people shouldn’t leave their homes for funerals / as they shouldn’t smell the dead (?). And now let me tell you about the funeral ceremony: / more people participated in the funeral of a small child / than in those of important people from the city / if there were 20 people, it was already large. And this was so different from before the plague: / if one died, he was lying in his house / for up to two days, as this was more honor / and people arrived also from outside town to pay their respect. During this epidemic, when a person had just died / in the same hour he was taken to church already / there was no wake on the same day / nobody present with the body, but he was buried |

Buccio di Ranallo, pp. 242-243. | Translation by Martin Bauch |

| 1348-00-00-Aquila4 | 1348 JL | About duration of the illness and help for the sick duringt the Black Death in Aquila. | Una gra‘ pigitate ch’era delli amalati, / era delli parenti che li erano mancati; / non era chi guardarli a tante necessitati; / tri carlini la femena chiedea li dì passati. Facio Dio una grazia delle amalanzie corte, / che uno dì, duj , tri durava male forte, / e quatro allo più alto chi era disposto a morte; / d’aconciarese l’anima le ienti erano acorte. (...) La granne pïetate si fo de li amalati / ca era apocati li omini, non erano procurati; / chi conperava guardia per essere aiutati, / lu dì e la nocte femena, petia tri grillati. |

One should piety those ill persons / who had no parents or relatives left / nobody took care of their needs / and helping women costed three carlini each day. A short illness was considered a divine favour / who suffered violently one, two three days / and a maximum of four days until death / people were aware to save their souls. (...) It was pitiful with all the sick people / as so few remained, they were not taken care for / whoever payed people to get help / a women for day and night, paid three carlini |

Buccio di Ranallo, pp. 243-244. | Translation by Martin Bauch |

| 1348-00-00-Aquila5 | 1348 JL | About practices of making testaments during the Black Death in Aquila. | Tamanta era paura, che onde omo tremava / la morte ciaschesuno ongi iurnno aspectava; / più che del corpo, l’omo de l’anima penzava; / quanno era sano e salvo, chi savio era testava. Or chi vedesse prescia a iudici e notari, / che era nocte e iurnno dalli testamentari; / e illi consideranno petiano asai denari / testemoni medemmo, a trovare erano cari Quanno omo cercavali e quilli demanavano: / ‚E scricto lo testamento?‘ se nno, ca no ci anavano; / si dicea ch’era scricto, allora s’abiavano; / no che daventro intrasero, m’a la porta rogavano. Anche vi mecto in dicere que conmenente è stato, / quanno fo la mortauta, se l’uomo avia testato / con iudici e notari e testemonij rogato, / se tosto non era in carta de coro publicato. Se omo a duji jornni o a tri regia per lu stromento, / de iudici e notari trovava impedimento, / c’alcuno era amalato o era in falimento, / o qualche testemonio gito era al gra‘ convento. Chi volea lo rogo fare relevare, / lo notaro un florino volea adomandare; / tanto petea lo iudice per volerse senare, / l’omo poi accordavase, se non potea altro fare. |

So large was fear, that everybod trembled / And expected to die any day / people were more preoccupied with their souls / and made their testaments as they were still healthy. You have seen how hastily people went to judges and notaries / to make their testaments day and night. / and those asked high prices, considering the risk / and it was expensive to find the necessary witnesses. When people searched them and the witnesses asked: / ‚Is the testament written?‘ If no, they didn’t come / if it was written, they agreed to come / but didn’t enter the house, just talked at the door. And I wanted to tell how it was in general / during the mortality when testaments were made / with jugdes and notaries and witnesses asked / if the document wasn’t published immediately. If a man returned after some days to get the testament / he found the judge or notarly not available / as some where ill or already about to die / or some withness had passed away. Who wanted to secure the juridical act / had to pay the notary a florin (gold coin) / so he would ask the judge to sign immediately / people accepted this, there was no other way. |

Buccio di Ranallo, pp. 244-245. | Translation by Martin Bauch |

| 1348-00-00-Aquila6 | 1348 JL | About the wealthy survivors of the Black Death in Aquila. | Li pochi che remasero, ciascuno ricco era, / per l’anima de‘ morti ne davana a rivera, / li clirici godiano la domane e la sera, / e ariccaro li urdini e tucte monastera. Li laici medemmo gaudiano volentero, / c’aveano delle cose p’ongi loro mistero; / per tanto poco preczo multe cose vennéro, / tre tanto vale mo: credateme ch’è vero. Quanno fo la mortauta, anni mille correa / e trecento e quaranta octo, così be‘ Dio ci dea; / tamanta fo paura che onn’omo temea, / multo altrugio renniose, chi morire credea. Chi facia testamento, null’omo che testava, / né parente né amico già no lli demannava / che cobelli lassaseli, ca no se nne curava, / le cose avia per niente c’a morir se pensava. O quante penetute de questo vi so‘ state, / che non se provedero de ’ste cose passate, / che ricchi potiano essere delle cose lassate, / che invidia hebbero a chi de ciò sono ariccate. |

The few who surved were all rich then / for the souls of the deceased they gave a lot / the clergy took advantage of this day and night / and religious house and monasteries got rich. But also lay people profited a lot / to their surprise, they had everything now / prices were suddenly so low for many things. / hardly a third; you can believe me. When the mortality was, in the year thousand / and threehundred and forty eight, as the good Lord decided (?) / as everybody was full of fear / much was given to who had feared to die. One had made a testament, or had ben a witness / had no parent or friend left / who could be made a heir / as he had feared to die in vain. Oh how much penitence was achieved / by those who didn’t accept goods then / how rich could they have got from the inheritance / what envy they had for those who enriched themselves. |

Buccio di Ranallo, pp. 246-247. | Translation by Martin Bauch |

| 1348-00-00-Aquila7 | 1348 JL | Social and moral effects of the Black Death in Aquila: New marriages and people leaving monastic communities, becoming greedy and mad in the eyes of the chronicler. | Scorta la mortaute, li omini racelaro; / quili che non l’aveano la mollie se pilliaro / e lle femene vidove sì sse remaritaro: / iuvini, vecchie e citule a questo modo annaro. No tanto altre femene, vizoche e religiose, / multe jectaro lo abito e vidile fare spose, / e multi frati dell‘ ordine oscire per queste cose, / omo de cinquanta anni la citula piliose. Tamanta era la prescia dello rimaritare, / che tante per iorno erano, no se poria contare; / non aspectava domeneca multi per nocze fare; / non se facian conzienzia de cose ch’eran care. (...) La iente fo mancata e l’avarizia cresciuta; / danunca era femina ch’avesse dote manzuta; / da l’uomo che più potea da quello era petuta, / peio ci fo che questo, c’alcuna fo raputa. Demente erano uscite da quelle gra‘ paure / della corte malanze con le bianullie dure, / de sadisfare l’animo poco era chi se cure, / a crescere ad ariccare puneano studio pure. |

When mortality came to an end, people felt relief / those who had no wife, looked for one / and the widows married again / young, old and children behaved the same way. And other women, even nuns / threw away their clothes and they became brides / and many friars left their order for the same reason / and men of fifty years married young girls. So large was this urge to marry again / so many marriages a day you couldn’t count it: / They didn’t wait for Sundays to marry / and they ignored how expensive everything had got. (...) People had become less, but greed increased; / every women had an extraordinary dowry, / and she married the man who could provide most, worst of all, some were even robbed (?). In a state of madness they had left the great fear / of the rapid disease with the hard buboes / to satisfy their souls if they had been cured / they turned their minds to enrich themselves only. |

Buccio di Ranallo, pp. 248-250. | Translation by Martin Bauch |

| 1348-00-00-Aquila8 | 1348 JL | A general dearth of foodstuffs and other goods after the Black Death in Aquila. | Chi vedesse la che se vennia a macellio! / Giamaj i‘ nulla citade no llo vidi sì bellio; / tante some ne ’sciano che paria u‘ ribellio; / chi non avia denari, ’cidease lu porcellio. Come fo gra‘ mercato, inanti, delle cose, / così se rencaro, dico, per queste spose; / panni e arigento e quello che allora abesongiose, / eranto tante care che se veneano oltragiose. Secte carlini viddi dare inelli pianilli, / cinque e quatro carlini e sei nelli cercelli, / e quatro e cinque solli jo ci vidi li anelli, / delli panni no dicovi, ca foro cari velli. |

And incredible how people ran to the butcher! / They had never been so rich in any city before: / They all ran for meat as if there was a riot / who didn’t have money, killed his own piglings How big demand there was for all things / that’s why it became so expensive for weddings / cloth and all kinds of things you would need / became expensive beyond all limits Seven carlini for shoes / Four to six carlini for round earrings / four to five soldi for a little lamb / and I won’t mention linen, as is was so expensive |

Buccio di Ranallo, p. 248. | Translation by Martin Bauch |

| 1348-00-00-Avignon | 1348 JL | Origins of the Black Death beyond the sea, its way via Naples to Montpellier and Marseille, and its impact in Avignon. | Postea, videlicet anno Domini MCCCXLIX., [p. 422] presertim in partibus ultramarinis et aliis vicinis, qualis a tempore diluvii non est facta, aliquibus terris hominibus penitus vacuatis multisque trieribus in mari cum mercimoniis, habitatoribus extinctis, sine rectore repertis. Marsilie episcopus cum toto capitulo et quasi omnes Predicatores et Minores cum dupla parte inhabitancium perierunt. Quid in Monte Pessulano, in Neapoli et aliis regnis et civitatibus actum sit, quis narraret? Multitudinem moriencium Avinione in curia, contagionem, morbi, ex qua sine sacramentis perierant homines et nec parentes filiorum nec e contra nec socii sociorum nec famuli dominorum curam habuerant, quot domus cum omni suppellectile vacue fuerunt, quas nullus ingredi audebat, horror est scribere vel narrare! Nulla fuit ibi causarum agitacio. Papa inclusus camere habenti ignes magnos continue nulli dabat accessum. Terrasque hec pestis transibat, nec poterant philosophantes, quamvis multa dicerent, certam de hiis dicere racionem, nisi quod Dei esset voluntas. Hocque nunc hic, tunc ibi per integrum annum immo pluries continuabantur. | Later, namely in the year of our Lord 1349, especially in overseas regions and other neighboring places, such devastation occurred as had not been seen since the time of the flood, with entire lands emptied of people and many ships left in the sea with their cargoes, their inhabitants extinct, and no leader found. The Bishop of Marseille, with his entire chapter, and almost all the Dominicans and Franciscans, along with half of the inhabitants, perished. Who could recount what happened in Montpellier, in Naples, and other kingdoms and cities? The multitude dying in Avignon, the contagion, the disease from which people died without sacraments, neither parents for their children nor vice versa, nor companions for each other, nor servants for their masters, had care, how many houses were left vacant with all their furnishings, which no one dared to enter— it is horrifying to write or tell! There was no debate of causes there. The Pope, confined to his chamber with large fires continually burning, granted access to no one. And this plague spread across lands, and philosophers, though they spoke much, could not give a certain explanation of these things, except that it was the will of God. And thus, now here, then there, throughout the entire year, indeed repeatedly, it continued.. | Matthias de Nuwenburg Chronica 1924-40, pp. 421-422. | Translation by Martin Bauch; None; |

| 1348-00-00-Avignon01 | 1348 JL | Arivval of the Black Death in many cities and regions of Southern France and Italy and consequences like changing burial habits, collapsing social bonds and abandoned settlements. | Eodem anno (1348) in Avinione, Marsilia, Monte Pessulano, urbibus Provincie, immo per totam Provinciam, Vasconiam, Franciam per omnemque mediterranei maris oram usque in Ytaliam et per urbes Ytalie quam plurimas, puta Bononiam, Ravennam, Venetias, Januam, Pisas, Lucam, Romam, Neapolim, Messanam et urbes ceteras epydimia tam ingens, atrox et seva violenter incanduit, quod in nullo dispar sexu, in etate nulla dissimilis, masculos et feminas, senes et juvenes, plebem et nobiles, pauperes, divites et potentes, precipue tamen plebem et laycos generali fedaque tabe delevit. Interimque lues oborta populum conripuit et depopulata est, ut in plerisque locis ministri sepeliendorum funerum primum multitudine cadaverum gravarentur, post difficulter invenirentur, post non sufficerent, et tandem penitus non essent. Jam etiam magne domus et parve per totas urbes, immo et urbes quam plures vivis hominibus vacue remanserunt et mortuis plene. In urbibus et domibus et campis et locis aliis opes et possessiones copiosissime, sed nulli penitus possessores. Denique tam sevi tabescentium etiam sub tectis et in stratis suis cadaverum putores exalabant, quod non solum in urbibus ipsis vivendi, sed etiam ad ipsas terras et urbes appropinquandi per duo milia passuum non erat facultas hominibus, nis inficerentur, subito (p. 274) corriperentur, post triduum morerentur, et jam nec sepilrentur. Et, ut paucis expediam, tam ingens, tam pestifer ignis epydimalis conflagravit, ut non, quantum hominum in partibus illis absumpserit, sed quantum reliquerit, inquirendum videatur. Vir uxorem et uxor virum, mater filiam et illa matrem, pater filium et e converso, frater sororem et illa fratrum et sororem, et postremo quilibet quemlibet amicum tabescere incipientem contagionis timore reliquit. | In the same year (1348), in Avignon, Marseille, Montpellier, the cities of Provence, indeed throughout entire Provence, Gascony, France, along every coast of the Mediterranean Sea up to Italy, and through many cities of Italy, such as Bologna, Ravenna, Venice, Genoa, Pisa, Lucca, Rome, Naples, Messina, and countless other cities, an epidemic so immense, fierce, and cruelly violent broke out that it spared no one of any sex, age, neither male nor female, nor exempt from any age group, afflicting men and women, old and young, commoners and nobles, the poor, the rich, and the powerful, especially the common people and laypersons, with a general and foul contagion. Meanwhile, the plague that had arisen seized the people and laid waste to them, so that in many places those responsible for burying the dead were first overwhelmed by the multitude of corpses, then one struggled to find them, later there were insufficient of them, and finally they couldn't be found at all. Now, both large and small houses throughout the cities, indeed, even many cities, were left empty of living people and full of the dead. In the cities, houses, fields, and other places, riches and possessions were abundant, but there were no owners anywhere. Finally, such a severe contagion of those wasting away caused the stench of corpses to waft even under roofs and in their beds, such that not only was there no opportunity for people to live in the cities themselves, but even approaching the lands and cities within a distance of two miles was impossible for people, unless they got infected, suddenly seized (p. 274) and died after three days. They were no longer buried. And, to summarize briefly, such a great, such a deadly epidemic fire raged that it seems not only necessary to investigate how many people it consumed in those regions, but how many it left behind. A husband abandoned his wife, and a wife her husband; a mother her daughter, and she her mother; a father his son, and vice versa; a brother his sister, and she her brothers and sisters; and, finally, everyone abandoned anyone at the first sign of the disease's spreading out of fear of contagion. | Heinrich von Herford 1859, pp. 273-274. | Translation by Martin Bauch |

| 1348-00-00-Bohemia | 17 January 1348 JL | Following astrological phenomena a formerly unheard of epidemic raged in Bohemia as well as in other parts of the world (Christian and pagan) for 14 years. And there was no hideout from it neither in the lowlands nor on the mountains and many people died. | Eodem anno die XVII Ianuarii fuit eclipsis lune, et coniunccio quorundam malivolorum planetarum, ex quibus coniunccionibus et malis constellacionibus orta est inaudita epidimia seu pestilencia hominum in universo mundo et duravit tam in Boemia quam in aliis mundi partibus per XIIII annos proxime sequentes, et iam ibi, iam illic in terris christianorum et paganorum ubique. Nec erat alicubi refugium, quia sicut in planis sic in montibus et silvis homines moriebantur. In omnibus locis fiebant foveae grandes et plures singulis annis predictis, in quibus moriencium corpora sepeliebantur. Talis pestilencia et ita longa nunquam fuit a seculo. | In the same year on January 17 there was a eclipse of the moon and a malevolent conjunction of the planets and resulting from these conjunctions and bad constellations there was an unheard of epidemic or human plague in the whole world which lasted as well in Bohemia as in other parts of the world for 12 successive years at one time here at another there everywhere in the Christian and pagan lands. There was nowhere a hidout to be found, but as well on the flat land as in the mountains and forests the people died. In all places numerous and large grave pits where made in every single of the above mentioned years, in which the dead bodies where buried. Such a plague that lasted to long had never happend in this age. | Beneš Krabice of Weitmil, Cronica ecclesie Pragensis, in: Fontes rerum Bohemicarum, vol. IV, ed. Emler (1884), pp. 457-548, 516 | Translation by Christian Oertel |

| 1348-00-00-Bologna | May 1348 JL | Black Death in Bologna | Maxima et inaudita mortalitas fuit Bononiae, quae vocata fuit et semper vocabitur la mortalega grande, quia numquam fuit aliqua similis. Et incoepit de mense maji et duravit per totum annum et fere fuit per totum mundum et tam magna, quod duae partes ex tribus partibus personarum firmiter decesserunt; inter quos decesserunt duo doctores bononienses per totum mundum famosissimi, videlicet dominus Johannes Andreae, decretorum, et dominus Jacobus de Butrigariis, legum doctores | The greatest and unprecedented mortality was in Bologna, which was called and will always be called "the great mortality," because there was never anything like it. It began in the month of May and lasted for the whole year, and it was nearly worldwide and so severe that two out of every three people certainly died. Among those who died were two of the most famous doctors in the world from Bologna, namely, Master Johannes Andreae, a doctor of decrees, and Master Jacobus de Butrigariis, a doctor of law | Griffoni 1902, p. 56 | Translation by Martin Bauch |

| 1348-00-00-Bologna 002 | 1348 JL | Black Death in Bologna. | Fu il maggior terramtto che mai fosse stato al mondo il giorno della Conversione di San Paolo, e poi tutta la stade fu gran mortalitade per tutto il mondo, e morevano gl'huomini d'un enfiasone, che li veniva sotto la lasina overo nel' angonara, e puoco stavano amalati. | It was the greatest landfall that had ever been in the world on the day of the Conversion of St Paul, and then the whole stade was great mortality throughout the world, and men were dying of emphasisation, which came to them under the leaves or in the 'angonara', and they were sick. | Croniche succinte di Bologna, p. 95v. | Translation by DeepL |

| 1348-00-00-Bologna-Bohemia | 1348 JL | After descrbing the effects of the Black Death in many parts of Europe, Francis states on Bohemia: Students travelling from Bologna to Bohemia saw a lot of dead and severely ill people. Most of the students died as well already on the way. | Eodem tempore quidam studentes de Bononia versus Boemian transeuntes viderunt, quod in civitatibus et in castellis pauci homines vivi remanserunt et in aliquibus omnes defuncti fuerunt, in multis quoque domibus, qui vivi remanserant et egritudine oppressi, unus alteri non potuit porrigere haustum aque, nec in aliquo ministrare, et sic in magna affliccione et anxietate decedebant. Sacerdotes quoque ministrantes sacramenta et medici egris medicamenta ab ipsis inficiebantur et moriebantur et plurimi sacerdotibus mortuis sine confessione et sacramentis ecclesie de hac vita migraverunt. Facte sunt autem fosse magne, late et profunde, in quibus corpora defunctorum sepeliebantur. In locis quoque pluribus infectus aer plus inficiebatur — qui plus nocet quam cibus corruptus — ex putredine cadaverum, quia non remansit superstes, qui sepeliret. Verumtamen de prefatis studentibus nisi unus fuit Boemian reversus sodalesque sui in via decesserunt. | At that time, certain students who were travelling from Bologna towards (versus) Bohemia saw that few humans remained alive in the cities and castles and in some, all were dead. In many houses, those who survived were so overcome by the disease that one could not carry a drink of water to another nor care for another in any way. Thus they withdrew in great torment and anguish. Priests ministering the sacraments and medics supplying medicaments got infected and died and many priests died without confession and the sacraments of the church and they moved away from this life. And in many places, the air became further infected from the rotting of corpses, becoming a greater threat than spoiled food, as no one survived to bury them. Of these students, only one returned to Bohemia. His companions died along the way. | Francis of Prague, Chronicon Francisci Pragensi, ed. Jana Zachová, Prague 1997, p. 204f. | Translation by Christian Oertel |